The haka in Parliament and the Treaty Principles Bill

David Seymour, the Atlas Network, and the latest attempt to snuff out Māori sovereignty

Kia ora all, I hope that the two-thirds of my subscribers who reside in Aotearoa are enjoying their summer in this great land of ours, and I guess also the 10% who are Australian. I’ve been trying to get out and make the most of it, enjoying a place with some of the best beaches and bush in the world. I hope that you’ve been able to find some time for that too. Apart from a bit of a break, I’ve been working on some things in the background, and it seems that 2026 is certainly going to be an interesting year. This upcoming national election is shaping up to be a highly consequential one, and if the cooker circles are anything to gauge, a very strange one indeed. In light of Seymour’s promise to “reignite” the Treaty Principles debate this year (and Waitangi Day next month), I thought I’d reshare this thread from November 2024, when Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke led a haka in Parliament in protest of the Treaty Principles Bill, and what it looks like when lobby groups hijack elections.

You’ve probably seen the video of Te Pāti Māori performing a haka in New Zealand’s Parliament in protest of the Treaty Principles Bill by now. It’s reached close to a billion views combined at this point, and reactionary media has been quick to jump on it as some sort of “stone age” display (as if protest has never been a part of parliamentary politics before). You might even hear people say that the bill they’re protesting is about “equal rights”, and what this current government just wants is an honest discussion about what the Treaty means. This is all a smokescreen for what the Treaty Principles Bill is actually about: rewriting history to protect extractive capital.

Meet David Seymour, current leader of the ACT Party. He’s somehow even more off putting in person. Seymour joined Young ACT at university, the right-wing “libertarian” party founded by the post-1984 Labour neoliberals who thought they didn’t go far enough. They ransacked a state with large public corporations, and let their friends carve it up for the highest bidder.

This wave created a new oligarchy class, with key figures who cultivated mechanisms useful for their goals. Alan Gibbs was one of the most prominent, involved with the NZ Business Roundtable and the NZ Initiative. If you want to get a picture of Gibbs’ character, here’s a video of him describing lining up the New Zealand Forestry Service’s fleet of equipment and putting up for auction. Gibbs is “the godfather” of ACT, and it serves as a way for him to push his vision for New Zealand, shared by other likeminded ideologues. “I’d privatise all the schools, all the hospitals, and all the roads”, he once told a party conference in 2014. “We've had a 20-year siesta so I think Act should get out there and shake the market.”

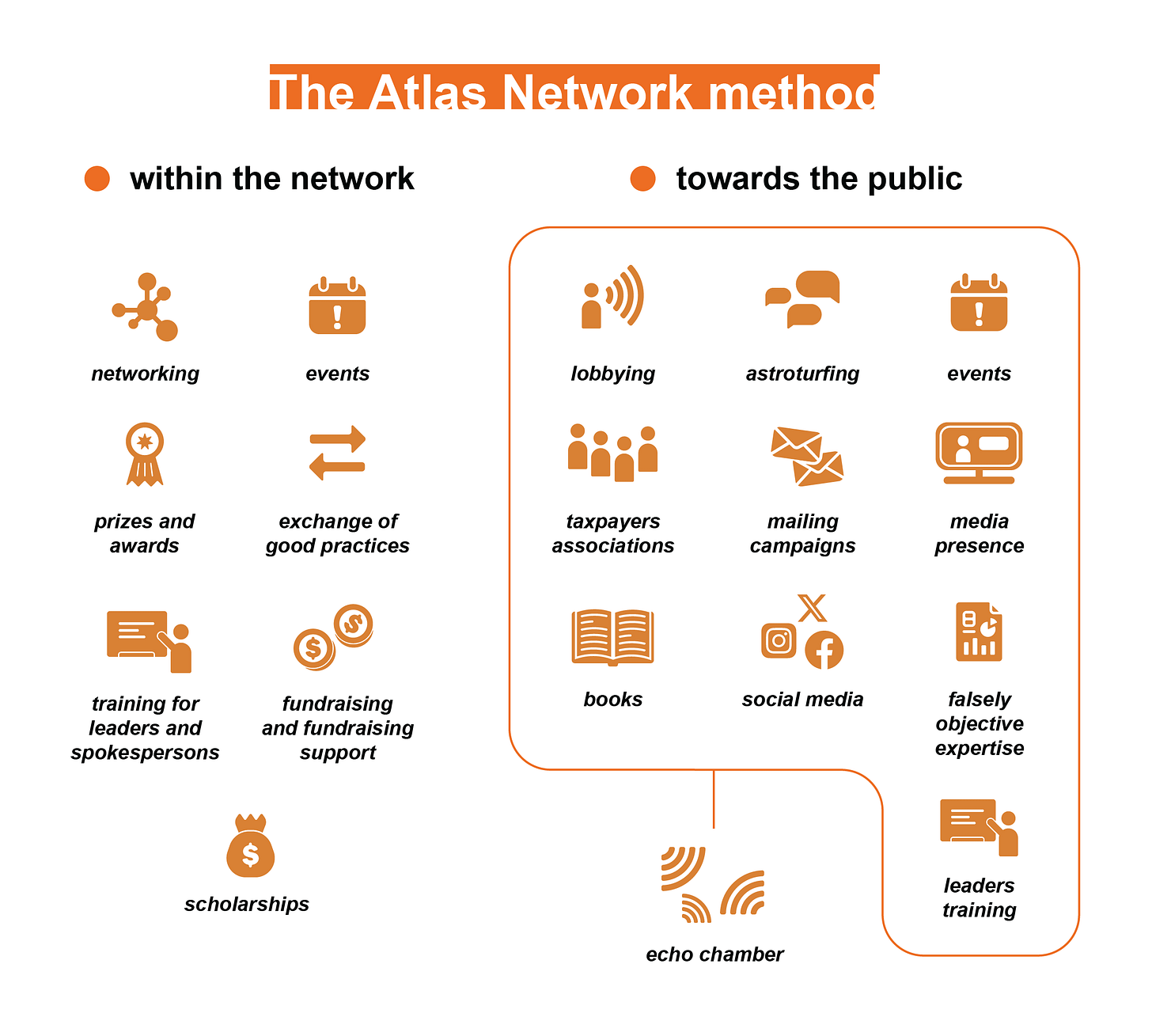

But ACT can also be seen as part of a wider push, one tentacle of the Atlas Network, a think tank incubator founded in 1981 by British entrepreneur Antony Fisher. Described as a “think tank that creates think tanks”, the Network seeks to cultivate and connect like-minded organisations that push Austrian School-inspired libertarian free market policies. Quickly spreading in the 1980s after endorsements from Margaret Thatcher, F.A. Hayek, and Milton Friedman, and a long relationship with the Koch brothers, the Atlas Network now boasts 600 partner organisations in over 100 countries.

They have been described as “the predominant vehicle for fossil capital’s global mobilisation against climate science and policy”, helping elect far-right governments and running astroturf/botting campaigns. They were instrumental in helping Trump, Milei, Bolsonaro and others come to power, and were a crucial part in drafting Liz Truss’ austerity budget. They push for devastating cuts designed to play on populist messaging of “gutting the bloated state”, and massive deregulation, often for extractive industry interests. They do this at whatever cost, flooding the system with whatever tactics they think will work to manufacture consent.

Prospective Atlas Network underlings can go into the global system, intern at a few different think tanks, go to some training sessions, and meet likeminded people. They come out with experience in spin doctoring, pushing talking points, and dirty politics tricks. They can then go set up their think tanks at home with initial support from Atlas, before quickly connecting to favourable domestic interests. Any guesses who the current Atlas Network chair is? Why, it’s Debbi Gibbs, Alan Gibbs’ daughter.

The reason I lay this out is David Seymour, after seemingly trying and failing at engineering, decided to sell his soul and enter the Atlas Network system. Here he is putting on a fake Canadian accent to argue against public transport in the 2000s. Seymour worked for Atlas-connected think tanks in Canada, one of their most active fronts for anti-climate policy. He participated in training sessions, including songwriting contests about charter schools with the Atlas Network CEO, Brad Lips (pictured below).

After cutting his teeth in Canada, Seymour returned to New Zealand and becomes leader of the ACT Party in 2014. He worms his way into respectable discourse by debasing himself as a “meme” to paper over ACT’s questionable reputation. He goes on Dancing With The Stars, tells Women’s Weekly “I’d give it all up for love”, visits high schools for meet and greets (and gets fond of Snapchatting students), trying to present himself as anything other than a complete skinwalker. But he still harbours deeply reactionary politics, and bides his time for the opportune moment.

That’s where the Taxpayers’ Union (TPU) comes in. The TPU is another Atlas Network think tank, founded by Jordan Williams and David Farrar in 2013, a year before Seymour is made ACT leader. Williams was a disciple of the Key-era National attack dogs like Cam Slater and Farrar, taking lessons from them and overseas taxpayers’ unions to create a right-wing lobbying firm that can be dressed up as a “Concerned Citizens” group. They are the private lobbying wing of the forces behind ACT, and alongside others like the NZ Initiative, they push a coordinated set of policy and soundbites. The TPU funds a 24/7 media hotline for comment any time of the day. They’re so committed to reducing wasteful government spending that they file millions’ worth of frivolous OIA requests, and took out $60,000 in COVID wage subsidies. They have also been caught astroturfing protest movements, and it shows their wider strategy: capitalising off reactionary anger to serve their end goals of reducing regulation and oversight for industries, and further cannibalisation of the state.

In 2020, the Labour government told the farming industry (paraphrasing here) “Can you please do some planning on water usage and pollution? Nitrate readings are 30x the level where it starts affecting childbirth in some areas.” The farming industry replied “over my dead body”, and the Groundswell protests were born. Groundswell took on the classic appearance of “the little farmer taking on the big bad state”, with tractors marching through major cities protesting against being given the burden of looking after the environment, similar to scenes in Europe over recent years. Groundswell’s demands were to stop regulations on water use, exempt themselves from climate change policy, remove the “ute tax”, etc. But Groundswell was an astroturf campaign, with a domain name was registered by the TPU and initially promoted on their mailing list. It was an orchestrated effort to protect one of the largest interest groups in New Zealand politics: animal farming.

35% of NZ land is owned by animal farmers. Cattle farming, especially dairy, has grown significantly in recent decades. 95% of dairy is exported overseas, primarily to serve as milk powder filling in chocolates. It is also, of course, incredibly destructive to the environment. Groundswell was the industry’s attempt to push against regulation, using the TPU and their dedicated lobby group, Federated Farmers, to turn it into an off and on national news story for months. But their biggest issue was Three Waters, the plan to bring water infrastructure under larger, publicly-owned regional bodies due to increasing costs and financing issues. Regional Māori iwi would also sit on the boards and have equal voting rights to local government. To talk about New Zealand’s somewhat unique form of “co-governance” between Māori and the Crown, we have to take a brief history lesson on te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Treaty of Waitangi).

To heavily simplify its history, the Treaty was signed in 1840 between a group of Māori chiefs and British representatives. Māori at the time outnumbered Europeans 80,000 to 2,000. It followed a previous Declaration of Independence signed by northern iwi in 1835. The treaty (and previous declaration) were drafted due to concerns of land theft and lawlessness on the part of Europeans, and encroachment from other colonial powers like France and Russia. The British government wanted further assertion of their control over the islands. The Māori version, the copy signed by both parties, agreed to let the British manage kawanatanga (governance), while Māori retained tino rangatiratanga (sovereignty/chieftainship). It outlined a system of shared authority, where Māori systems of self-governance could coexist with a British system. The English version differs, where Britain gains “sovereignty” instead of “governance”, and “chieftainship” is instead “undisturbed possession of lands”. These differences in meaning, arguably intentional, eventually led to the New Zealand Wars. Settler demand for land and increasing crackdowns on Māori sovereignty drove decades of conflict and land theft, followed by systemic attempts to wipe out Māori society. Turned into a segregated underclass, many Pākehā believed the “Māori question” would be solved by time.

But that never happened. A hīkoi (march) in 1975 led to the government finally recognising the treaty in law and establishing the Waitangi Tribunal, a legal body meant to investigate breaches of the treaty. In 1985 this was backdated to include historical claims up to 1840. The “principles of the treaty” started being invoked as a way for the tribunal, and other institutions, to refer to what the “spirit” of the document was, and what implementing that in a modern society might look like. The English version is only 578 words, not exactly a novel. But there in lies the problem: recognising the treaty opened Pandora’s box. As claims began to come into the tribunal, and Māori begun challenging the status quo, the government began to realise what actual reconciliation might look like.

In 1989, after axing the Department of Māori Affairs (in part due to a scandal orchestrated by the CIA), Labour PM David Lange laid out a loose set of “principles”, setting the bounds of what the government believed honouring the treaty would mean in a “practical” sense. Legal scholars argued it was a “definite and cynical attempt to redefine the treaty”. In effect, these have been the “guiding principles” since (while still violated repeatedly on this very limited definition). Arguably, there has been growing cooperation with and recognition of Māori by successive governments, even if limited or non-existent in many areas. But for New Zealand’s elite, any Māori oversight in government decision making is bad. They’re going to try stop you from polluting waterways, digging up the ocean floor for minerals, or selling mining licenses for $1 a year, and they might have mechanisms to actually stop you.

So the right, spurred on by ACT, TPU and others, began pushing co-governance as a political issue to manufacture consent. It started with Three Waters, fear-mongering about infrastructure being taken out of “Kiwi hands” and given to the “Māori elite”. There were a number of propaganda campaigns to push this further, including a “Stop Co-governance” national roadshow, where former street preacher Julien Batchelor told old white New Zealand, especially first generation British transplants (Ten Pound Poms), that Māori were coming to institute a new apartheid. Of course Batchelor would know, as he grew up in colonial Kenya before moving to New Zealand when the British left. He somehow acquired the funds to distribute 250,000 booklets promoting his talks and spreading fears designed to tap into the psyche of this group.

This was among a number of tricks used to force co-governance as an issue, that played especially well with an increasingly reactionary portion of the country looking for easy blame after lockdowns and post-pandemic economic shocks. Riding off of this, Seymour announced his Treaty Principles Bill (TPB). He said it was about “equal rights”, but in effect it would nullify any recognition of rangatiratanga or the relationship that Māori and the Crown have, pushing Māori-Crown relations back to the 1950s. It received objections from all corners of society, including prominent Māori, legal scholars, church leaders, and most living ex-PMs. However, the 2023 election became a vote partly on the “place of Māori in society”. The right focused on issues like bilingual road signs and ministry names, Three Waters leading to “Māori dominance”, axing the Māori Health Authority, slashing and burning the progress made in recent decades.

Like in most other countries, the incumbent centrist Labour Party lost heavily. ACT only received 8% of the vote, but Seymour was able to get the Treaty Principles Bill included in the right’s coalition agreement, supported by the other parties just for the first reading. National and NZ First let ACT lead them to the precipice, inciting major pushback. ACT is ramping up the temperature, and their coalition partners, with their own connections to the Atlas Network and the wider lobbying octopus, are able to play dumb and say their hand was forced. This parliamentary vote was the one that was protested by Te Pāti Māori last week, introduced 2 weeks earlier than expected to be overshadowed by the American election and get ahead of another hīkoi on Parliament.

The current coalition has spent the first year in office gutting the state and rolling New Zealand back decades, including restarting oil and gas exploration, firing thousands of public servants, creating a “fast-track” consent process which seems to mostly apply to their donors and friends, hiring tobacco and gun lobbyists to rewrite laws, opening military-style “boot camps” for youth offenders, trying to privatise the school and health systems, cancelling planning reform and infrastructure projects, and of course, throwing Three Waters onto the bonfire. I’m sure private industry will be able to step in and handle water infrastructure the way they’ve handled the power grid. The usual backroom dealings of a National government are fully out in the open.

You cannot believe them when they say that the Treaty Principles Bill is an “honest dialogue” on what the document means. It’s an attempt to tear it up and sell the last they can squeeze out of Aotearoa to the highest bidder. It might not pass now, but it’s not the end. ACT is now trying to turn the bill into a global culture war issue, where Western chauvinists like Matt Walsh can pick up half-baked talking points and treat it like another sideshow to throw popcorn at. The haka in Parliament was a protest against a government that has rejected norms, procedures, and any shambolic sense of democracy to push through destructive policy after destructive policy, trying to bring the country back to a time where “Māori knew their place”. Most people should be able to see it for what it is, indigenous people standing up against the agents of global capital and saying “we shall not let this pass”.