Caught in a "Kill-Web": New Zealand and America's 2025 National Security Strategy

The Trump admin's new military and foreign policy direction, and New Zealand falling into lockstep

The past decade has seen the death rattle of the US-led “liberal rules-based order”, and many states, especially in the West, are responding to the turmoil by heavily re-militarising. We must prepare for uncertain and unstable times, we’re told, and that means investing 5% of GDP into the military. The Trump admin’s new 2025 National Security Strategy makes that clear, and reading it alongside what is happening in New Zealand spells out the direction our military policy is going.

The National Security Strategy (NSS) document, first issued by Bush Sr. in 1991, lays out the executive branch’s “national security concerns”, and how they plan to address them. Where does New Zealand and the Pacific sit into this strategy? Well, America is tired of its Global North allies who have not pitched in, especially against China.

We will build a military capable of denying aggression anywhere in the First Island Chain. But the American military cannot, and should not have to, do this alone. Our allies must step up and spend—and more importantly do—much more for collective defense.

States buy into the security umbrella through arms sales and favourable deals, shoulder more of the burden of running the empire, but get more favourable treatment from the US.

American policy should focus on enlisting regional champions that can help create tolerable stability in the region, even beyond those partners’ borders. These nations would help us stop illegal and destabilizing migration, neutralize cartels, nearshore manufacturing, and develop local private economies, among other things. We will reward and encourage the region’s governments, political parties, and movements broadly aligned with our principles and strategy.

New Zealand (and Australia) have long served as the regional managers of the Pacific, and as China has gained influence in the region, they’ve reverted back to a more colonial role. The past decade has seen more security agreements, war games, training, “freedom of navigation” exercises, and an increasingly aggressive tone from New Zealand on China.

Much of the groundwork for this re-alignment towards the US was laid by the previous Labour government, with Andrew Little spending his last year in office as Minister of Defence and intelligence signing numerous military agreements with Pacific neighbours. However, the NSS marks a large escalation in foreign policy from Biden, and even the first Trump term. The first three on the list of “America’s core foreign policy interests” read:

• We want to ensure that the Western Hemisphere remains reasonably stable and well-governed enough to prevent and discourage mass migration to the United States; we want a Hemisphere whose governments cooperate with us against narco-terrorists, cartels, and other transnational criminal organizations; we want a Hemisphere that remains free of hostile foreign incursion or ownership of key assets, and that supports critical supply chains; and we want to ensure our continued access to key strategic locations. In other words, we will assert and enforce a “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine;

• We want to halt and reverse the ongoing damage that foreign actors inflict on the American economy while keeping the Indo-Pacific free and open, preserving freedom of navigation in all crucial sea lanes, and maintaining secure and reliable supply chains and access to critical materials;

• We want to support our allies in preserving the freedom and security of Europe, while restoring Europe’s civilizational self-confidence and Western identity;

Put simply, America is telling Europe to start re-arming (later on “we expect our allies to spend far more of their national Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on their own defense”) while it militarises the Western Hemisphere and Asia-Pacific in preparation against China.

The Indo-Pacific is already the source of almost half the world’s GDP based on purchasing power parity (PPP), and one third based on nominal GDP. That share is certain to grow over the 21st century. Which means that the Indo-Pacific is already and will continue to be among the next century’s key economic and geopolitical battlegrounds.

Other lines point to preparing for more refugees (“prevent and discourage mass migration to the United States”), coordination on the now-combined Global War on Drug Terror (“governments cooperat[ing] with us against narco-terrorists, cartels, and other transnational criminal organizations”), and keeping China out (“free of hostile foreign incursion or ownership of key assets”). While these are talking specifically about the Western Hemisphere, this would likely extend further afield (“keeping the Indo-Pacific free and open”).

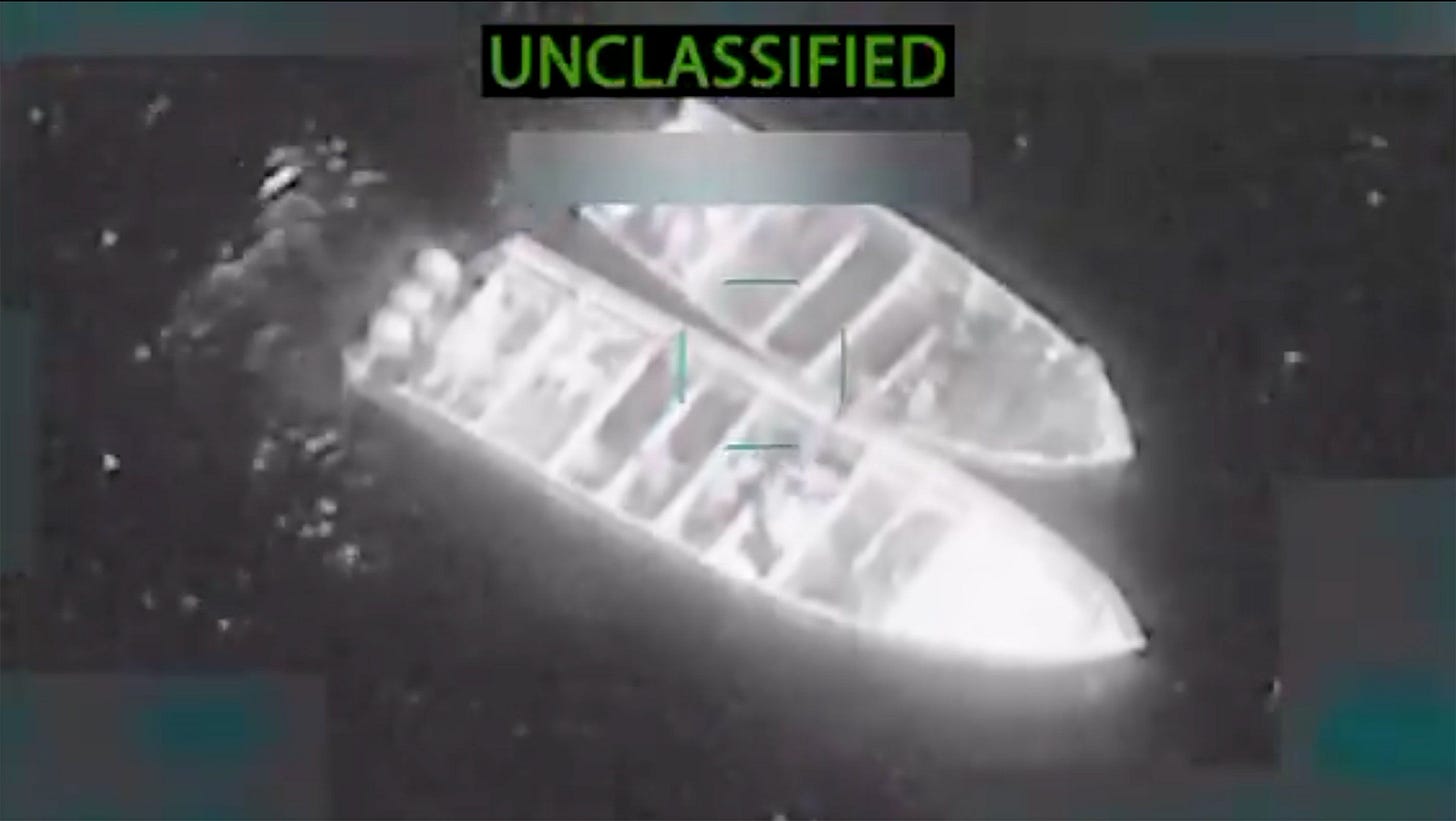

These are all plans that are currently unfolding with America flexing its muscles southwards into Latin America. The continent is experiencing a return of Operation Condor-style fascism to bring it back under heel after the most recent centre-left electoral wave. Far-right leaders like Bukele and Milei are engaging in austerity and crackdowns while cooperating heavily with the Trump admin. The Trump admin is currently trying to bully Hong Kong conglomerate Hutchison Holdings out of their stake in the Panama Canal. The Pentagon has killed at least 99 people so far in strikes on boats in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific to combat “narco-terrorists”, actions that are seemingly attempts by the Pentagon to push the bounds of what the US military can get away with. As of writing, the US has already escalated to a military blockade of Venezuela until it gives up land and oil “stolen” from the US. America is enacting what the NSS calls the “Trump corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine: they reserve final say over the affairs of the continent and beyond, and will use force to get their way.

This new era of American foreign policy requires allies to escalate accordingly, through investment, coordination, policy, and rhetoric. While the previous Labour government oversaw a creeping re-alignment towards the USA under Trump I and Biden, the coalition government has accelerated this process, and now Trump’s plans for a heavily militarised future are being enacted. Judith Collins, serving as Minister of Defence, Space, and the intelligence agencies, has been the figure charged with overseeing New Zealand’s new security and military policy. Trump took office January 20th, and on the 22nd Collins spoke to 1News ahead of the release of NZDF’s 15-year strategic plan.

“We have enormous resource wealth in this country. All these sorts of things make us vulnerable and we also have a real obligation to our Pacific neighbours, to work with them, to help them to protect their fishing grounds and their own sovereignty. Now we’ve got a big role to play and we should never rule out the fact we have to defend ourselves.

“We cannot only be the really nice people who come in and sort out the terrible mess after earthquakes and volcanoes, and all those sorts of things that happen. We do need to have a serious lethality component.”

Collins announced the government would be investing over 2% of GDP into the NZDF over 4 years back in April, the same month a military co-operation agreement was signed with the Philippines, a First Island Chain country. In August she announced a $2b purchase (originally budgeted for $300-600m) of five Lockheed Martin helicopters through a US government defence purchase program. She made a “secret” visit to Ukraine in September to look at how New Zealand can integrate the technologies being battle-tested on conscript after conscript, before meeting with UK officials to sign a new defence cooperation agreement.

FBI Director Kash Patel visited in July for some smiling photo-ops and the opening of an FBI office, one that he said would help counter China’s Pacific influence. Collins then visited Washington D.C. in October to discuss “how we might further bolster our long-standing defence and security partnership” and “potential opportunities for closer collaboration with one of our closest partners”, as New Zealand builds “a more combat capable defence force, with enhanced lethality and interoperability”. Collins later told the Post that

“They see us as an extremely valuable player, even though we’re obviously smaller than other partners. They really like the fact that we’ve been stepping up on deployments, that we are growing our defence force and its capability.”

What kind of conversations do you think she had with these people?

It’s interesting that the government would announce an action plan against meth trafficking in November that includes police, Customs, NZDF, Navy, and the GSCB running cross-agency “maritime operations” against drug syndicates operating in the Pacific. The Trump admin later that month sent out a diplomatic cable to all Western US embassies, asking them to “begin collecting data and reporting on migrant-related crimes and human rights abuses facilitated by people of a migration background”, and to let governments know that “the United States stands ready, willing, and able to support them in handling what we see as an existential crisis (migration)”.

New Zealand is also being enmeshed into the “kill-webs” that America is constructing across the Pacific through frameworks like Five Eyes and AUKUS. Pacific researcher Marco de Jong’s piece “Network empire: how advanced military tech is reshaping Five Eyes” lays out these developments:

In practice, the NZ Army’s pursuit of interoperability has led to deeper data integration through its Network Enabled Army project, Plan ANZAC, and the ABCANZ Armies programme. With the goal of contributing a motorised infantry battle group to an Australian Brigade within a US-led division, the NZ Army has begun linking its tactical sensors into Australian and multinational effector networks. During the US-led multinational Project Convergence Capstone 2025 experiments, the Defence Force sought to integrate with its Five Eyes partners and “[experiment] with NZ Sensor and Fires systems, enabled by networked C2 systems”, contributing to “a combined targeting process”. Put simply, our drones, their missiles, shared system.

Handwritten notes from a Five Eyes meeting in Britain acquired by Nicky Hager show that the intelligence sharing network is turning into an explicit military alliance under Anglo-American leadership. A huge focus was on the Asia-Pacific region, and preparing for a conflict with China: “A central part of the plan presented in Portsmouth... was to ‘develop a credible and effective combined joint all-domain [command and control] capability for counter-PRC Operations.’”

Without signing onto AUKUS, without formally re-engaging in ANZUS, and without much public debate, New Zealand is rapidly fusing into the American smart-tech war machine that is being constructed against China. Albeit, New Zealand has always played a crucial role in the formal and informal Anglo military alliance following WWII. While we officially severed our participation in ANZUS in 1985, we still remained a floating satellite dish for Five Eyes, and now produce guiding components for smart bombs and launch military satellites, all most recently used in Gaza. There have been moments where we’ve deviated from the pack. There have also been many times when a government has led us headfirst into fighting for the empire that America inherited from Britain.

The 1951 waterfront dispute (Part 2 coming soon) illustrates how easy it can be for the government to sign on the dotted line. In 1950, PM Holland announced at a Commonwealth PM summit in London that “New Zealand would stick by [America] through thick and thin and through right and wrong”. Days later, he flew to Washington D.C. to meet with President Truman and the men who were currently shaping what would become the American Century, to sign that proverbial deal with the devil. Is Holland’s declaration in 1950 that far from what current ministers and officials are saying, or doing?